Greg Roskovensky

Femoroacetabular Impingement in Athletes

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, FAI is a condition in which the bones of the hip are abnormally shaped. Because of the abnormality, the articulation of the femoral head and the acetabulum rub together and can cause irritation. FAI is more common in elite athletes than the general population. Today, we're going to talk about FAI and how we can better manage the long term development of athletes prone to FAI.

Wolf's Law

Wolf's law is the basis of what we do as strength and conditioning, rehab professionals, or coaches. Wolf's law basically states that a healthy person's bone will adapt to the loads and demands of which it is placed. Other tissues (muscle, tendon, ligament) have the same principles that can be applied. This is how we improve strength and function in ourselves and our athletes.

HIP ANATOMY

The hip joint complex consists of the femoral head's articulation with the acetabulum of the pelvis. The hip is a ball and socket joint and is covered with a thin layer of cartilage. The hip joint is deepened via the labrum, which is a a fibrocartilaginous rim that surrounds that hip socket. The hip joint capsule connects directly into the labrum which helps in many ways including keeping the joint pressure similar. Disruption of the labrum can lead to pressure changes and early degeneration of the hip complex.

A number of muscles directly or indirectly play a role in the hip joint stability and mobility factors.

|

Anterior hip (generally flexors) |

Posterior Hip (Extenders or Rotators) |

|

Psoas Major Iliacus Rectus Femoris Sartorious TFL Adductor Group (Help Flex hip from extended position) |

Gluteus Maximus Gluteus Medius Gluteus Minimus Hamstrings Piriformis Deep External Rotators (Ext/Int obturators, Inf/Sup gemelllus) Adductor Group (help extend hip from flexed position) |

http://classroom.sdmesa.edu/eschmid/F08.23.L.150.jpg

Other “core” muscles such as the rectus abdominus, obliques, transverse abdominus, paraspinals, quadratus lumborum, Lats (via thoracolumbar fascia) attach to difference aspects of the pelvis or sacrum and can play a role in static and dynamic postures.

Femoral anteversion is a change in anatomy, born with or acquired, in which the head and neck of the femur is rotated anteriorly. Someone with femoral anteversion will have what appears to be excessive hip internal rotation with a reciprocal loss of external rotation. Anteversion can also lead to sub-talar pronation, tibial/femoral IR, and anterior pelvic tilt. Core and posterior chain strengthening is key in this athlete.

Femoral retroversion could be seen as the opposite. This appears to be excessive hip external rotation with a loss of internal rotation. This is important to know when training your athletes. Since these players have decreased hip internal rotation, the closed chain IR of shooting may be more difficult and/or painful.

Femoroacetabular Impingement

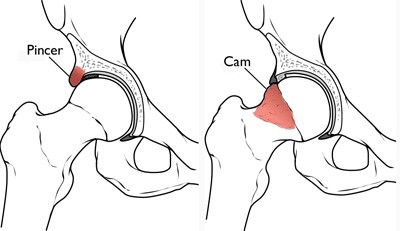

FAI can be broken down into two distinct types and some can exhibit a mixed presentation in which those individuals can have both types at once.

In a CAM type FAI, the femoral head is not round and cannot perfectly rotate within the acetabulum. A bony formation appears on the edge of the femoral head which grinds onto the inside of the acetabulum.

In a Pincer type FAI, the impingement occurs due to extra bone that extends over the normal rim of the acetabulum. The labrum, in addition, can be crushed under the prominent rim.

Image from AAOS.org

How do FAI's form in our hips and why are athletes more prone to these abnormalities? In the general population, there is some evidence for a genetic component to developing hip deformities. The last few years has brought an abundance of research on the topic and the athletic population is definitely more prone to FAI and hip deformity and has been hypothesized that the vigorous stress placed onto the hip in the transfer of energy from the LE to the pelvis and spine can speed this process. FAI generally increases the rate of development of Osteoarthritis to the fourth and fifth decades of life, but is now being seen in those in their 20s and 30s.

Pain may be gradual in onset but often there is a single event that may set off pain. When further questioned, the athlete may report nonspecific groin type symptoms. They may also report not being very flexible. Hip symptoms generally emanate from anterior groin and medial thigh. Often, there is a C-sign associated with FAI.

Research suggests that any force greater than 3x body weight can increase the joint's risk of early degeneration and if even one of these muscles function is decreased, the compression force can exceed 4x's body weight (18,26 of current concepts). Further joint instability or increased joint laxity can even further create this risk.

There is also research available to state that many people, young and old, can have radiographic evidence of FAI, osteoarthritis, and other pathologies who are fully asymptomatic. This can include “significant” pathology such as disc herniation pathology, degenerative changes, and other age and activity based changes.

Quick Assessment of Femoracetabular Impingement

Let's talk about a few measures you can use to determine whether your athlete may have a predisposition to FAI or other hip issues.

Rock Back

Your athlete should be able to maintain a neutral spine and rock his/her butt back towards their heals. If they are unable to maintain the neutral spine position, this may indicate a hip flexion deficit due to FAI. Make sure to keep athletes out of an anterior pelvic tilt.

Craig's Test for Femoral Torsion

Performing the test: Test limb's knee is placed in 90 degrees of flexion. Rotate the hip medially and laterally while palpating the greater trochanter area until the outward most point in the lasteral aspect of the hip is prominent. Greater trochanter is parallel to the floor.

A normal value would have your tibia slightly outward 8-15 degrees. More than 15 degrees would put you into anteversion, less than 8 degrees and you would have retroversion of the femur.

Posture and exercise technique checks should also be completed but these two above assessments are easy ways to assess anatomy and it's role in exercise selection.

Life and Training Implications of Femoroacetabular Impingement For the Hockey Player

A study by Philippon et al reported that a significant number of young hockey players have signs of FAI and labral tears. Ages 10 up to 18, the prevalence only gets larger as time goes on with these athletes. Many with FAI, Cam or Pincer types end up with restricted hip flexion and hip internal rotation.

Your athletes should be educated on avoiding positions that actively cause their symptoms, particularly until their symptoms are no longer present. Sitting fully flexed in a chair all day may not be the best way of getting through your day. Squats and lifts from the floor may be particularly problematic. A bigger topic in physical therapy at this time is using language that is non-threatening in nature. Suggesting that someone is a train wreck or an injury waiting to happen may not be the best approach. If someone moves poorly and has poor mobility, focus on the chance to improve rather than the worst-case scenario.

A postural assessment can also go a long way. Hockey players often live in their anterior pelvic tilts. Someone in APT often has a difficult time with hip flexion. Posterior chain and anterior core strengthening in a neutral spinal position can go a long way in improving hip flexion in your athletes. Medial soft tissue work can also break through some of the stiffness and tightness from all that eccentric adduction the game brings.

If you assess your athletes, things like push-ups and planks done correctly in a neutral spine are much more difficult than hanging out on your hip flexors like many people tend to do. Find the right position and make sure your athletes know exactly when they lose it. Training to this technical failure will go far in helping your athletes understand when they are in and then they aren't in good positions.

Deadlifts from a higher start position (rack pulls), loaded bridges (bilateral or SL), hip thrusters are all good ways of attacking the glutes. It's my opinion that athletes should be competent at the bilateral version of exercises (and movement patterns) before making them unilateral in nature, however, single leg exercises may allow for increased hip variability when approaching end range flexion, are used with less resistance, and can spare other areas of the body (spine). If you need to squat, ½ squat or box squats are likely the way to go. Lamontagne et al found in a 3-D analysis of hip movement during maximum squat that the FAI group was unable to squat as low as a control group of matched subjects.

We also want to make sure that flexors are long and strong as the natural skating motion lengthens the hip flexors and they must be able to work eccentrically throughout their entire necessary motion.

For mobility drills, consider a lateral (or superior to inferior) distraction using a jump stretch band during rock back exercises with the hip in slight internal and external rotation. Do not actively cause pain but the feeling of end range can be a good thing. Also, focus on other mobility drills that you normally use to clear up anterior pelvic tilt.

In conclusion, hip problems and FAI can become huge issues in younger and older hockey players alike. It is necessary to make sure that your exercise selection makes sense in terms of not only general physical preparedness and sport-specific training but also in terms of your individual athlete's anatomical potential. Paying attention to detail can go a long way in getting and keeping your athletes out of pain.

References